Using Artificial Reefs to Measure and Promote Invertebrate Populations

Brayden Bluse

04/15/2025

Alaska Pacific University

Abstract

Artificial reefs are increasingly used to enhance marine biodiversity and support ecosystem health, particularly in regions experiencing habitat degradation. This study evaluated the colonization patterns of invertebrates on artificial reef structures installed in Smitty’s Cove, Whittier, Alaska. Using ceramic settlement plates connected by PVC and anchored to the seafloor, we monitored invertebrate colonization over an eight-month period through underwater video, physical collection, and species identification. We observed a consistent increase in species density over time, with Sitka periwinkle snails (Littorina sitkana) and green sea urchins (Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis) emerging as dominant species. Less abundant taxa such as limpet snails (Lottia pelta) and chitons (Polyplacophora) appeared later in the study, likely influenced by behavioral traits such as homing and habitat familiarity. Species distribution on the structures was also influenced by microhabitat preference, depth, and grazing efficiency. Our findings suggest that fixed artificial structures can successfully support ecologically relevant invertebrate communities in high-latitude environments, and their design can be optimized based on species-specific behaviors and ecological roles.

Introduction

Biodiversity is essential for ecosystem health, and this can be promoted and measured by installing artificial reefs (Seaman, 2009). Prince William Sound is an important region for commercial, subsistence, and recreational fish harvest (Reynolds, 2007). These reefs would help promote a number of species; as well as invertebrate that many fish feed on. An efficient use of artificial reef data would be to show the residents of Prince William sound and/or broadly Alaskan residents the importance of placing these reefs. Settlement plates give a good estimate of invertebrate populations in an area and can give you sufficient data if used properly. The type of material used can be important, as species rely on different refuge dimensions and textures. Organisms with weak or insecure attachments to substrate have a greater chance of death and should settle in a quality refuge (Walters 1996). Knowing the required refuge dimensions of species will give you an idea of what material is best suited for those species. Using different refuge dimensions can give a more accurate measurement of ecological health as you get more of a variety of species settling, as you provide a variety of refuge. Water quality is another important factor when determining ecological health. In a study done by Paul Snelgrove with colonization trays in a muddy habitat, he says, Total densities of organisms were higher in Depression Trays compared with Flush Trays on each sampling date, and of the five taxa that were consistently abundant, four were significantly more abundant in Depression Trays (bivalve larvae, gastropod larvae, juvenile Mediomastus ambiseta (Hartman) polychaetes, and nemerteans)” (Snelgrove, 1994). Depression trays, being the deeper trays, had higher densities of colonization, but there did not seem to be a solid reason as to why. This is presumedly a result of larvae being entrained in the depression trays (Snelgrove, 1994). This means that hydrodynamics and behavioral factors play a big role in colonization.

Colonization on artificial reef structures could be Influenced by things such as tide and water circulation, which can be affected by boats and water traffic as they move water. Stationary plates are generally used, as they provide an anchor point. Floating habitat can be beneficial for some species, but they have some downsides. Floating installations had greater flow velocities and shear stress compared to fixed ones (Perkol-Finkel, 2006). This is a suitable habitat for shrimp species but does not give a good measurement for overall health of an ecosystem as only some species can thrive in these types of habitats, as a lot of species rely on a safe and stationary environment to grow. Another factor that can affect these structures, arguably the biggest, is urban development. The provision of extra hard substrata presents additional free space, and recent research suggests non-indigenous epifauna may be able to exploit these artificial structures (particularly pontoons) more effectively than native species (Dafforn, 2009). Artificial reefs can have negative affect if not thought out properly. These structures can promote the growth of species that are not good for the overall ecological health, which causes more damage. Future management strategies should take into account the potential for shallow, moving structures to enhance invader dominance and strongly consider using fixed structures to reduce opportunities for invaders (Dafforn, 2009). This is why fixed structures are more widely used as they are easier to monitor and control.

The type of material used can lead to a significant difference in the number of invertebrates that settle, but the deployment methods make no difference (Field, 2007). Materials that work best in tropical environments may work just as good in cold water, but that cannot be certain, as there are several different environmental differences between the two. This makes it important to choose the right medium that allows colonization but also makes it easy to remove invasive species and to easily observe what is on the material for accurate documentation. The development of these areas also adds a somewhat new problem for Alaska’s costal habitats as there is a steady increase in erosion and pollution. Although well studied in tropical and temperate locations, less is known about settlement plate efficacy in high latitude locations (Levy, 2017). Studies that have been done in tropical, and more importantly temperate conditions (as it’s a closer representation and in latitude), are a great starting point for settlement plates in high latitudes. Studies have already been done in Smitty’s Cove, Whittier which show promising results. A study on the Artificial Reef that is currently in Smitty’s Cove shows that there was an increase in Sebastes spp (Levy, 2017). If there are fish being attracted to these reefs, then there must be an abundance of invertebrates (food) also at these structures (NOAA).

Methods

Structure Construction

The artificial reef structures were made out of 2” x 2” ceramic tiles with a hole drilled out for a PVC connector and attached by silicon (Figure 3). Silicon allowed for flexibility and durability against the wear and tear of the tide. These plates were then connected by pieces of PVC that were specifically measured for precise spacing; the spacing was determined independently to see what is preferred by invertebrates. A length of PVC with a serrated end was placed at the bottom so that it was easier to install the structure and secure it to the sea floor.

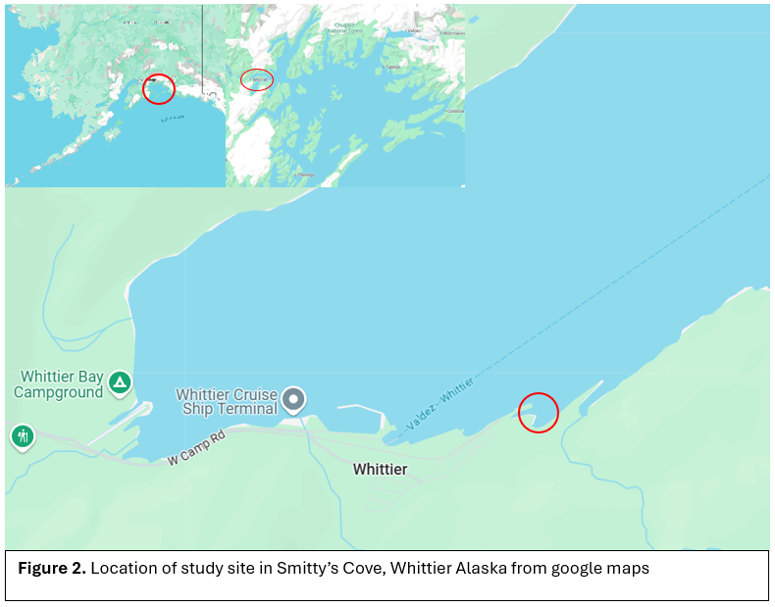

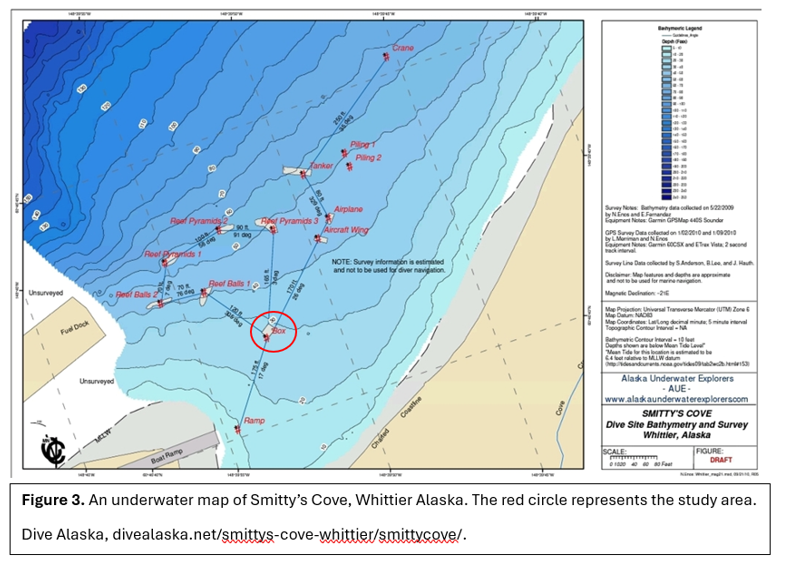

Deployment

We installed our structures near a structure, “the Box” (Figure 2). The Box is rusted out and colonized by feather duster worms and other invertebrates. Prior to the dive, the structures were pre-assembled and then placed in Smitty’s Cove, Whittier AK (Figure 1). The structure was placed in the sediment.

Observation Dives

We recorded date, time, temperature (F), salinity (parts per thousand and specific gravity), Visibility (ft), wind speed (mph), and wind direction. Date, time and temperature were taken from an aqualung dive computer. A water sample was also collected during each dive and tested to record salinity. Visibility was measured with a Secchi Disk and a long measuring tape. Wind speed and direction was gathered from the Marine Weather app. This was recorded from a buoy near Whittier. Each dive, we video recorded the structures with a GoPro. We used the GoPro Hero9 until October 20th, then switched to the GoPro Hero7. Videos were then downloaded to a laptop to be analyzed. Through analysis we counted the number of species, how many of each species, and species density. This was not a precise count as not all of the videos were clear due to visibility, but there was enough to get an understanding of invertebrate populations over time. Richness (number of species) and dominance (species that have the highest population) were recorded and used for analysis to understand what species are colonizing on these structures and at what rate.

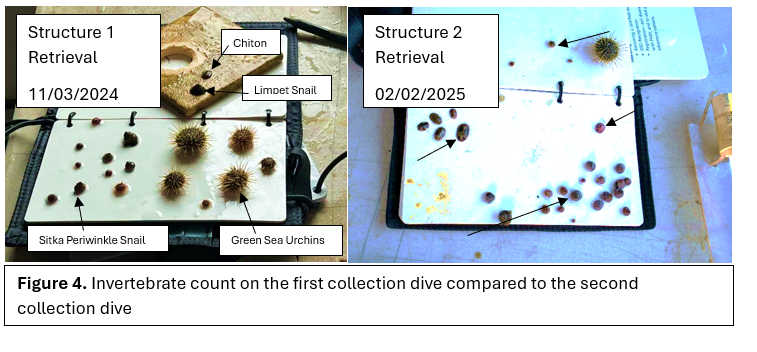

After five months post-installation one of the structures was inspected and we counted the abundance of invertebrates by species. This data represents the colonization that occurred before die off. The second structure was pulled eight months after installation to see what remained after die off. The structures had to be collected meticulously to ensure that no invertebrate were knocked off into the water column. This was achieved by putting a plastic bag over the structure during collection to ensure we get a count of all invertebrates that were on the structure. As soon as the structure were taken out of the water, we took photos of the structure, each plate, all the invertebrate together on a dive slate and each species individually. The structure was designed to come apart, so the plates were separated and laid out to ensure quality photos are taken of each individual plate.

Results

Species density overall increased when comparing the two collection dives (Figure 4). New species such as tube worms and a nudibranch were found on the second structure. The species that were observed on every video and collection dive were: Sitka periwinkle snails (Littorina sitkana), green sea urchins (Strongylocentrotus droebackiensis), limpet snails (Lottia pelta), and chiton (Polyplacophora; Figure 6). Periwinkle snails and green sea urchins were the most abundant in population on the structures. Limpet snails and chiton were the least dense in population. There was an increase in species density around the second collection dive in February after the gradual decline that started in August. No invertebrates were regularly seen using the aquarium structure and only diatoms settled.

Discussion

Sitka Periwinkle Snails were the most abundant on the structures (Figure6). Periwinkle snails, alone, are a good food source for native species and primary predators include the Red Rock Crab (Cancer productus) and pile perch (Rhacochilus vacca; Sylvia, 1999). Green Sea Urchins, being another abundant species, are mainly consumed by sea stars, crabs, wolf eels and other large fish, and sea otters (Himmelman, 2025). It can be assumed, based on the corresponding invertebrate, that predators that feed on them will be attracted to areas if their prey are in high enough density. Limpets and chiton did not seem to be attracted to these structures, at least within the time of this experiment, and can be assumed that their predators would not likely be attracted to these structures; unlike the periwinkle and green sea urchins that were abundant.

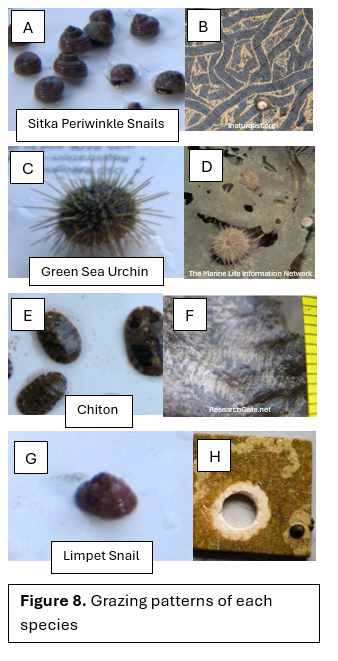

All four species eat algae as a major part of their diet. These artificial reef structures are a great growing median for algae, making it a great place for grazing. Each species exhibits variable grazing patterns are dependent on anatomy and speed. Limpet snails, although the least frequent, were the most efficient grazers as they were the only invertebrate with highly visible grazing tracks (Figure 9, H). Limpet snails scrape up algae with a radula, a ribbon-like tongue with rows of teeth (Heller, 1970). Sitka periwinkle snails eat diatom films and scrape filamentous algae and lichens from rocks and rockweed using their radula (David, 2003). Their feeding is similar to limpets and allows for visible, but faint, grazing trails (Figure 9, B). Green sea urchins eat kelp and other algae, and occasionally scavenge on fish and invertebrates (Himmelman, 2025). Green sea urchins primarily graze on kelp so no visible grazing patterns were found on the structures (Figure 9, D). Chitons eat algae, bryozoans, diatoms, barnacles and sometimes even bacteria (Potter, 2023). Despite the fact of chitons having a well-developed radula, there were no visible grazing patterns on the structures (Figure 9, F).

Chiton are slow moving creatures and have homing behavior (Chelazzi, 1990). This could explain why chiton showed up later as they were not familiar with the structures until later (Figure 8). Chitons have trail following behaviors and stick to familiar habitat, with the exception of foraging excursions (Chelazzi, 1990). Limpet snails also have homing behavior and usually follow familiar paths (Denny, 1984). Limpet snails like rocky shores and create indents in rocks that allow them to suction to it to lock in water during low tide (Denny, 1984). Limpet were observed following similar behavior as we saw the same trail appear within a few month period. Many rocky shores have been replaced with concrete sea walls that alter limpet snail movement patterns (Bulleri, 2004). The artificial structures we used may have had a similar effect, changing there habits. Due to the small size of the structure, it may not have been noticeable. These sea walls act like artificial reefs, and show that artificial reefs can be used as make-shift habitats (Bulleri, 2004). Although, it also shows that it can change how invertebrates interact with there environment as it is changed (Bulleri, 2004). Green sea urchins are known to travel over large areas while foraging (Green, 2022). Green sea urchins are great at locating energy-rich food and seem to go wherever the food is (Green, 2022). This is why we saw an increase in urchins right away and through the study as they were able to locate the structure that algae had been growing on. The green sea urchins were observed on all plates and went wherever the food was (Figure 8). Green sea urchin populations decrease with the increase in depth, but that can be reversed as the higher temperature at the surface allows for the rise in disease that can wipe out population at higher depths (Green, 2022). Periwinkle snails move above the tide line to avoid predation (Janice, 2003). Periwinkle snails were observed more on the top 2- 3 plates on the structure, and this could be due to this behavior (Figure 8). Periwinkle snails do not have homing behaviors and have been observed moving in random directions in search of food (Peter, 2003).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that artificial reef structures can effectively promote invertebrate colonization in high-latitude environments such as Smitty’s Cove, Alaska. The consistent presence and dominance of Sitka periwinkle snails and green sea urchins indicate that these structures provide suitable habitat and food resources for key grazers, which in turn may attract higher trophic predators. Observations of species-specific grazing behavior and spatial distribution suggest that structure design—including plate spacing, material, and placement—can influence both colonization rates and species diversity. Notably, species with homing behaviors, such as limpets and chitons, were slower to colonize, indicating the importance of longer-term studies to capture full ecological dynamics. These results highlight the potential of using settlement plates and artificial reef structures as tools for monitoring ecosystem health, promoting biodiversity, and informing sustainable coastal management strategies in Alaska. Future research should further explore the relationship between artificial reef design and invasive species management, hydrodynamic effects, and long-term ecosystem integration.

Acknowledgments

David Scheel, Karense Knightly, Ben Wilkins, and Zoe Munson

References

Bulleri F, Chapman MG, Underwood AJ. 2004. Patterns of movement of the limpet Cellana tramoserica on rocky shores and retaining seawalls. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 281:121–129. https://www.int-res.com/abstracts/meps/v281/p121-129/

Chelazzi G, Ferrarini F, Parpagnoli D, Santini G, Ugolini A. 1990. The role of trail following in the homing of intertidal chitons: a comparison between three Acanthopleura spp. Mar Biol. 105(3):445–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01316316

Dafforn, K. A., Johnston, E. L., & Glasby, T. M. 2009. Shallow moving structures promote marine invader dominance. Biofouling 25(3): 277–287.

Denny MW. 1984. Habitat selection and migratory behaviour of the intertidal gastropod Littorina littorea (L.). J Molluscan Stud. 50(1):1–13. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3948

Field, S. N., Glassom, D., & Bythell, J. 2007. Effects of artificial settlement plate materials and methods of deployment on the sessile epibenthic community development in a tropical environment. Coral Reefs 26: 279–289.

Green R, Scheelbeek P, Bentham J, Cuevas S, Smith P, Dangour AD. 2022. Growing health: global linkages between patterns of food supply, sustainability, and vulnerability to climate change. Environ Health Perspect. 130(7):077001. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP10025

Levy, C. 2017. Diver observations of community structure on a subarctic marine artificial reef in Whittier, Alaska. Marine Ecology Progress Series.

Perkol-Finkel, S., et al. 2006. Floating and fixed artificial habitats: Effects of substratum motion on benthic communities in a coral reef environment. Marine Ecology Progress Series 317: 9–20.

Peter S. Petraitis 2, et al. “Occurrence of Random and Directional Movements in the Periwinkle,Littorina Littorea (L.).” Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, Elsevier, 26 Mar. 2003, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0022098182901162.

Paul, V. R., Snelgrove, P. V. R., et al. 2003. Hydrodynamic enhancement of invertebrate larval settlement in micro depositional environments: Colonization tray experiments in a muddy habitat. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 287: 45–58.

Walters, L. J., & Wethey, D. S. 1996. Settlement and early post-settlement survival of sessile marine invertebrates on topographically complex surfaces: The importance of refuge dimensions and adult morphology. Marine Ecology Progress Series 137: 161–171.

Yamada, S. B., et al. 1999. Predation induced changes in behavior and growth rate in three populations of the intertidal snail, Littorina Sitkana (Philippi). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology.

Watson, D. C., et al. 2003. Dietary preferences of the common periwinkle, Littorina littorea (L.). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology.

Heller, J. 1970. Patellogastropoda: Limpets. In: SpringerLink.

Himmelman, J. H., & Steele, D. H. 2025. Foods and predators of the green sea urchin Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis in Newfoundland waters. Marine Biology. SpringerLink.

Janice H. Warren 1, et al. “Climbing as an Avoidance Behaviour in the Salt Marsh Periwinkle, Littorina Irrorata (Say).” Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, Elsevier, 31 Mar. 2003, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0022098185900796.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). n.d. Invertebrates. NOAA Fisheries. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from www.fisheries.noaa.gov/invertebrates.

Potter, G. 2023. What do chitons eat? Aquatic Live Food | Aqua Cultured Aquarium Foods. Retrieved September 27, 2023, from www.aquaticlivefood.com.au/what-do-chitons-eat/.

Seaman, W., & Lindberg, W. J. 2009. Artificial reef – An overview. ScienceDirect Topics. Retrieved from www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/artificial-reef.

Picture References

Shell of keyhole limpet [Internet]. Gainesville (FL): Florida Center for Instructional Technology; [cited 2025 Apr 10]. Available from: https://etc.usf.edu/clipart/72300/72322/72322-keyhole.htm

Iconfinder. [date unknown]. shell icon [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 10]. Available from: https://www.iconfinder.com/icons/4378029

Sea urchin icon [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 10]. Available from: https://thenounproject.com/icon/600502/

Periwinkle vector PNG, vector, PSD, and clipart with transparent background [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 10]. Available from: https://pngtree.com/freepng/periwinkle_5800662.html

NPDR-103 product page [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 10]. Available from: https://www.labnics.com/catalog/npdr-103

Creazilla. [date unknown]. Tides – free vector icons [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 10]. Available from: https://creazilla.com/nodes/94654-tide-icon

Pngtree. [date unknown]. Temperature level icon symbol, isolated, weather, indicator PNG [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 10]. Available from: https://pngtree.com/freepng/temperature-level-icon_5219734.html

Google Images. [date unknown]. Secchi disk icon transparent – Search Images [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 10]. Available from: https://www.google.com/search?q=sechi+disk+icon+transparent&tbm=isch